Visualizing Water Consumption: Non-potable vs Potable

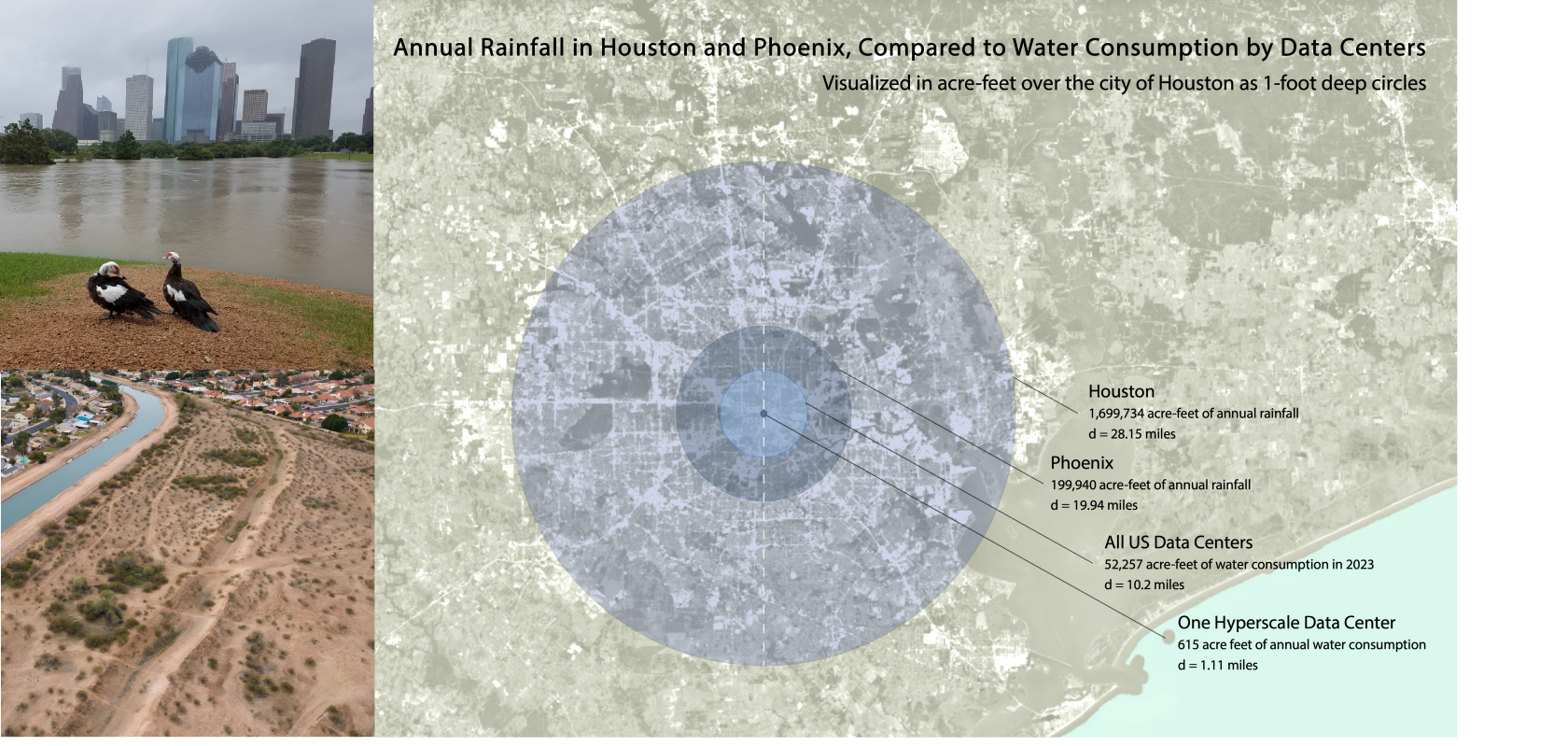

This figure highlights the contrast between city rainfall and the scale of water consumption by data centers. Houston, with nearly 1.7 million acre-feet of annual rainfall, receives more than eight times Phoenix’s 200,000 acre-feet. This is a reflection of their climates, the former being water-abundant and the latter drought-prone. When placed against these baselines, the water use of data centers appears smaller but remains very significant. In 2023, all U.S. data centers together consumed about 52,257 acre-feet of water—roughly a quarter of Phoenix’s annual rainfall. A single hyperscale data center alone uses around 615 acre-feet annually, visualized here as just over a 1-mile-wide circle.

Although total rainfall, even in drought-prone Phoenix, far exceeds the water consumption of data centers, the central issue is the type of water they use. Most data centers rely on potable, drinking-grade water rather than reclaimed or non-potable sources. For instance, Google reported that in 2023 only about 22% of its water withdrawals for data centers came from reclaimed or non-potable sources, meaning that the remaining 78% was potable water. This reliance means that data centers compete directly with local communities for limited supplies of drinking water.

The reason reclaimed water is not more widely used lies in both technical and regulatory challenges. Non-potable water can accelerate corrosion, scaling, and microbiological growth in cooling systems, which in turn shortens equipment life and increases maintenance. To manage this, engineers must regularly assess water quality, including pH, conductivity, total dissolved solids, chlorides, silicon, hardness, alkalinity, and microbial counts. They often need to work with local utilities to request additional treatment or to identify alternative sources that can reduce risks to equipment performance.

There are also practical barriers, such as using reclaimed water requires more frequent cleaning and specialized equipment to handle impurities. Permitting is often complex, and compatibility with treatment plants is not always guaranteed. Many areas also lack infrastructure such as purple pipe systems, which are designed to deliver non-potable water for industrial use. On top of that, advanced treatments such as ultrafiltration, ozonation, or reverse osmosis can make reclaimed water safer for cooling, but increase costs and add operational complexity.

Despite these challenges, some companies have made progress. Microsoft’s facility in Quincy, Washington, uses untreated irrigation canal water for cooling, relying on only about 5% potable water. To deal with mineral buildup and wastewater issues, the company and the city developed the Quincy Water Reuse Utility, a closed-loop treatment system that recycles cooling water and saves an estimated 138 million gallons of potable groundwater annually. Similarly, Amazon has also expanded its use of recycled wastewater, treating and reusing it by developing a plant-based treatment method using sphagnum moss to reduce chemical use while improving water quality. Moreover, Digital Realty in Singapore has deployed an electrolytic descaling system that prevents impurities from accumulating and allows water to be reused more times before discharge.

No comments to display

No comments to display